Wednesday 31 July, 2024

The First Webcam

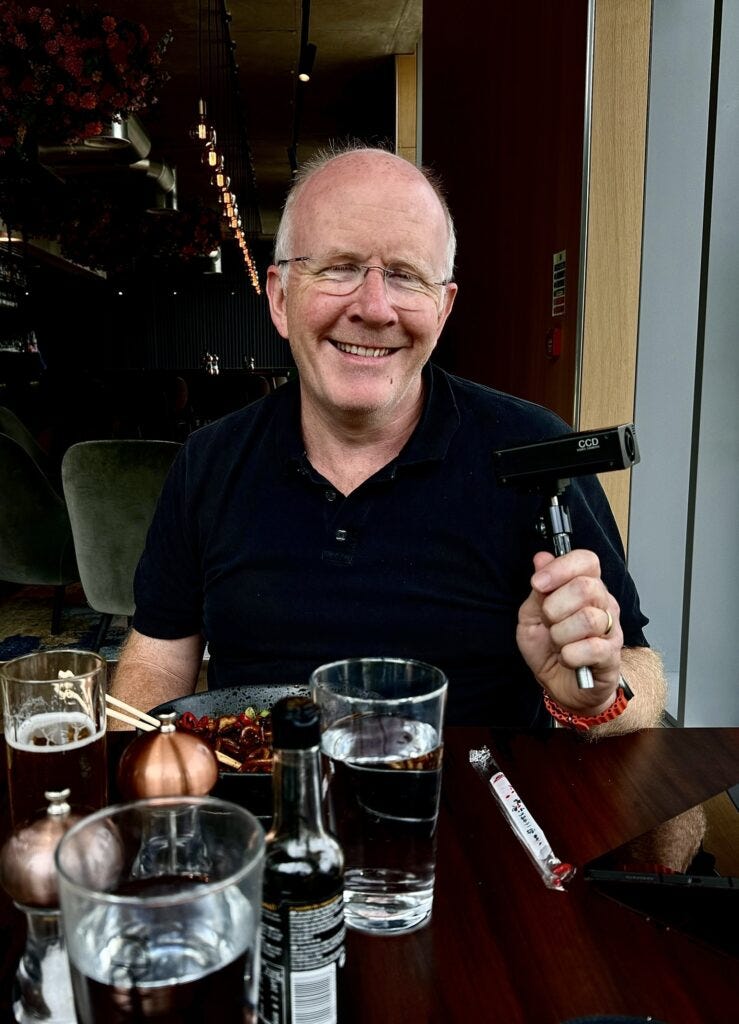

This was the world’s very first webcam. In 1991 my friend Quentin Stafford-Fraser and his colleague Paul Jardetzky set it up to watch a coffee-pot in the Cambridge Computer Laboratory’s Trojan Room (a large space previously occupied by an early mainframe computer) which housed a number of graduate students. Quentin and Paul connected it to the lab’s internal network so that graduate students everywhere in the building (rather than just the privileged denizens of the Trojan Room) — could see when the coffee had been brewed. Quentin wrote the X-Coffee program that displayed the live image in a small box on the top right-hand corner of every student’s desktop computer, and Paul wrote the server software to underpin it.

In 1993, when Mosaic — the first web browser that could handle images — appeared, the coffee-pot was hooked up to the Internet and broadcast on the web, and for a brief period was the most watched pot in the world! (Fittingly, it never boiled.) Many years later, when the Computer Lab moved from central Cambridge to its new, vast, building on the West Cambridge site, the venerable pot was auctioned for charity, and Quentin became the first person I’ve ever known who appeared on the front pages of the London and New York Times on the same day!

All of this was brought back by having lunch with him last week, when he suddenly produced the ancient relic from his bag. (It had been briefly liberated from its usual display case in the Lab for a TV interview he had done the day before.)

Quentin wrote a nice memoir of the webcam which was published in the Proceedings of the ACM in 2001.

Quote of the Day

”Me no Leica”.

Headline on Dorothy Parker’s review of Christopher Isherwood’s I Am A Camera.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

The Wailin’ Jennys | Light of a Clear Blue Morning

A distinctive take of a Dolly Parton song.

Long Read of the Day

Democratic fragility and resilience.

I know, I know, I/we pay too much attention to what’s going on in the US at the moment. That’s one of the curses of living in the ‘Anglosphere’, as my European friends often point out. But on the other hand, what happens in the US in the next 90-odd days will affect us all. If you doubt that, ask President Zelensky.

In brooding on it I’ve been oscillating between two frames of mind, both triggered by what James Joyce would have called epiphanies.

The first, triggered by Joe Biden’s disastrous performance in the televised ‘debate’ between him and Trump, was a memory of an afternoon many years ago when my youngest son was revising for his GCSE exams. He was sitting at the dining-room table while I was in the kitchen cooking supper and he suddenly exclaimed, “Dad, I’ve got it! Tragedy is when you can see the disaster coming but you know there’s nothing anybody can do about it.”

The second was a moment in 2013 when I was reading The Confidence Trap: A History of Democracy in Crisis from World War I to the Present by my friend and colleague David Runciman. In it he argued that democracies are good at recovering from crises but bad at avoiding them. The lesson they draw from their mistakes is that they can survive them — and that no crisis is as bad as it initially appears. This breeds complacency rather than wisdom, leading to the dangerous belief that democracies can muddle through anything. (The ‘confidence trap’ of the book’s title.)

The dangerous thing, of course, is that muddling through takes time, and if democracies are slow to appreciate the next crisis then there may not be enough time to adjust before it’s too late. Watching how agonisingly slow Biden and the Democrats seemed to be in realising the danger led me to conclude that muddling through was no longer an option and that the US would wind up in the grip of a fascist administration with all that implied.

But then Biden conceded to reality and suddenly light appeared at the end of the tunnel. It was an astonishing moment, and of course it may not in the end derail the Trump bandwagon, but there’s now a tangible sense that the US may not fall into Runciman’s confidence trap.

This sense of democratic resilience is admirably captured in a post by Helen Cox Richardson on her admirable Substack blog, which I recommend reading in its entirety.

Here’s how it opens:

Just a week ago, it seems, a new America began. I’ve struggled ever since to figure out what the apparent sudden revolution in our politics means.

I keep coming back to the Ernest Hemingway quote about how bankruptcy happens. He said it happens in two stages, first gradually and then suddenly.

That’s how scholars say fascism happens, too—first slowly and then all at once—and that’s what has been keeping us up at night.

But the more I think about it, the more I think maybe democracy happens the same way, too: slowly, and then all at once.

At this country’s most important revolutionary moments, it has seemed as if the country turned on a dime…

Do read the whole thing.

My commonplace booklet

Linkblog

Two plus two = 22?. Clever and instructive film about the MAGA mindset.

Thanks to Chris Hall for suggesting it. He uses it in his teaching.