Wednesday 28 September, 2022

Quote of the Day

”I’d do anything for caviar and probably did.”

Henry Kissinger — on visiting Moscow.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Mendelssohn | Overture ‘The Hebrides’ | LSO & John Eliot Gardiner

Long Read of the Day

Gareth Evans — philosophy’s lost prodigy

Nice memoir by Lincoln Allison in Engelsberg Ideas. Reading it, I was reminded of Keynes’s memoir of Frank Ramsey (another genius who tied tragically young) in his Essays in Biography.

University College, Oxford, October 1964: the economics fellow, David Stout, has assembled the twelve freshmen PPE students for their first class. This is an unusual procedure as lectures and individual tutorials are the normal means of teaching, but Stout is preoccupied with persuading any government and political party that will listen of the virtues of something called ‘value added tax’ and wants to meet all the students together. I am one of them and I have done none of the preparation for this class, being entirely preoccupied with such matters as rugby and new friends, but I am hoping that my ‘A’ and ‘S’ level economics from fifteen months earlier will enable me to get by. Actually, there are only eleven of us. Enter the twelfth to the traditional sarcastic remark from the tutor. The new arrival has long black hair and a black beard and wears a black scholar’s gown. With his hooked nose and rimless spectacles he seems like an edgy and hyperactive raven. He is carrying all six of the books recommended for the class which he deposits unceremoniously on the floor. ‘So this is economics?’ he demands and David Stout replies that these books are about welfare economics which is regarded by many as the foundation of the subject. ‘It’s based on a mistake,’ snaps the raven and the rest of the class is devoted to the tutor defending his subject from aggressive interrogation. It is increasingly obvious that the raven is at least the intellectual equal of the tutor…

Do read on.

Books, etc.

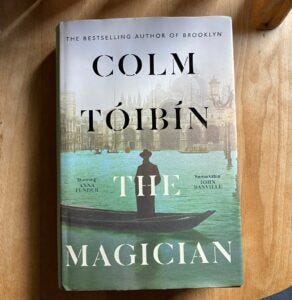

Just the Mann

My wife and I recently finished Colm Tóibín’s fictionalised biography of Thomas Mann. I was less impressed by it than the folks who eulogised it on its dust-jacket. You know the kind of guff — “a remarkable achievement” (John Banville); “a moving and intimate portrait by one master of another” (Anna Funder); “a great imaginative achievement — immensely readable, erudite, worldly and knowing” (Richard Ford); “no living novelist dramatises artistic creation as profoundly, as luminously, as Colm Tóibín, or conveys so well the entanglement of imagination and desire” (Garth Greenwell).

Contd. p.94, as they say in Private Eye.

I was surprised to be so disappointed by it because I had really admired The Master, Tóibín’s fictionalised biography of Henry James. But perhaps the reason is that Thomas Mann was a less interesting character than dear old Henry. Of course had, perforce, an interesting life because of circumstances beyond his control (first Hitler and, later, Joe McCarthy), but in this imaginary he comes across as a solipsistic bore. The really interesting character in the book turns out to be his remarkable wife, Katia — and, as chance has it, she actually wrote a memoir, so maybe that should be next on our list.

My commonplace booklet

Catspeak on Trump’s assertion that he can declassify documents at will.