Wednesday 20 April, 2022

Remembering Katherine Whitehorn

Readers with long memories will recall my tribute to Katherine in 2018 when it became known that she had advanced Alzheimer’s. She died in January this year and yesterday I went to her Memorial Service in London.

It was held in St James’s church in Piccadilly, which I’ve always thought of as the parish church of the Old Money that inhabits that part of London when it’s not residing in its grand country houses. You get the picture when you notice that the church’s grand piano is a Fazioli. Katharine was a very long-term Observer columnist and one of the most distinctive journalists of her generation, but she had been at one time the paper’s Fashion Editor, and yesterday her friends from that period — all of them in their eighties or even older — turned out, in style. And I mean style. I’ve never seen such an assembly of beautifully coiffed and elegantly attired women in my life. So it was fitting that Rachel Cooke, an Observer colleague who gave a lovely tribute, reminded the congregation of how sharp an observer of the couture scene Katherine could be. Think, for example, of her observation that “there are three kinds of hats: offensive, defensive, and shrapnel”, the last referring to the kinds of hats that find themselves attached to ladies’ heads at posh weddings.

She was a wonderful woman. May she rest in peace.

Apropos Virginia Woolf and Keynes

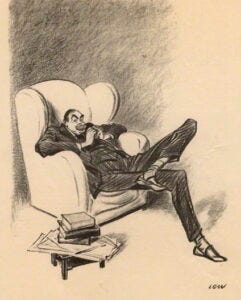

VW’s diary entry on Keynes yesterday prompted Andrew Curry (Whom God Preserve) to remind me about the famous Low cartoon of Keynes in his armchair, which captures the great man rather well.

Quote of the Day

”The wind of change, whatever it is, blows most freely through an open mind.”

Katherine Whitehorn

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Franz Schubert | Litanei auf das Fest Aller Seelen | Felicity Lott

This was sung beautifully by the Choir of St James’s yesterday.

Long Read of the Day

”You want to write letters to your city”

This is a transcript of a remarkable conversation between Ezra Klein and Volodymyr Yermolenko, a Ukrainian philosopher and the editor of the 2019 book, Ukraine in Histories and Stories, a collection of essays by Ukrainian intellectuals offering insights not only on Ukraine’s history going back to the Middle Ages and the Cossack era of the 16th and 17th centuries, but also on its recent past.

This is the passage that initially caught my attention:

EZRA KLEIN: This is a strange question to know how to ask correctly. What is it like to go from living in a city that is peaceful, where you’re working and doing your writing and shopping for groceries and checking your Facebook page and tweeting, all of a sudden to a city that is being shelled? What of your life before remains? What doesn’t? What does passing through that barrier from normalcy to emergency feel like?

VOLODYMYR YERMOLENKO: Well, a lot of things have changed very quickly in our understanding. Things have changed their meaning. For example, a window is no longer a window because you’d better not approach to the windows, people say, because if there is a shelling, you can be wounded by the glass of the window.

The light is no longer the light because the light can be dangerous if there are airstrikes. So you better switch off the lights when you are — in the evening, for example. Therefore, when you’re traveling through Kyiv right now on car — and I do it regularly — you are traveling in the dark streets. So the lights from the streets are switched off. So you are in a very dark place, which never, never happened before, of course.

And if you enter — I several times took some families to volunteer to get them out of the city, and then we went to other villages, for example, and when there is dark, the villages are completely dark. There are no lights in the houses, because people are very careful enough not to give signs to artillery or to airstrikes, to jets — the Russian jets — that there are villages.

So the meaning of things have changed. Of course, your understanding of your house, of your home. For example, I relocated my family. I spent some time with my relatives in western Ukraine. It’s very hard, actually, to lose your home. So I have an impression that your home, your house, your apartment is like the dearest person to you. So you want to come back. You want to write letters to your city, for example. You want to hug it, et cetera.

My commonplace booklet

A flyover view of Elon Musk’s new estate Link

Courtesy of Séan Doran and NASA.