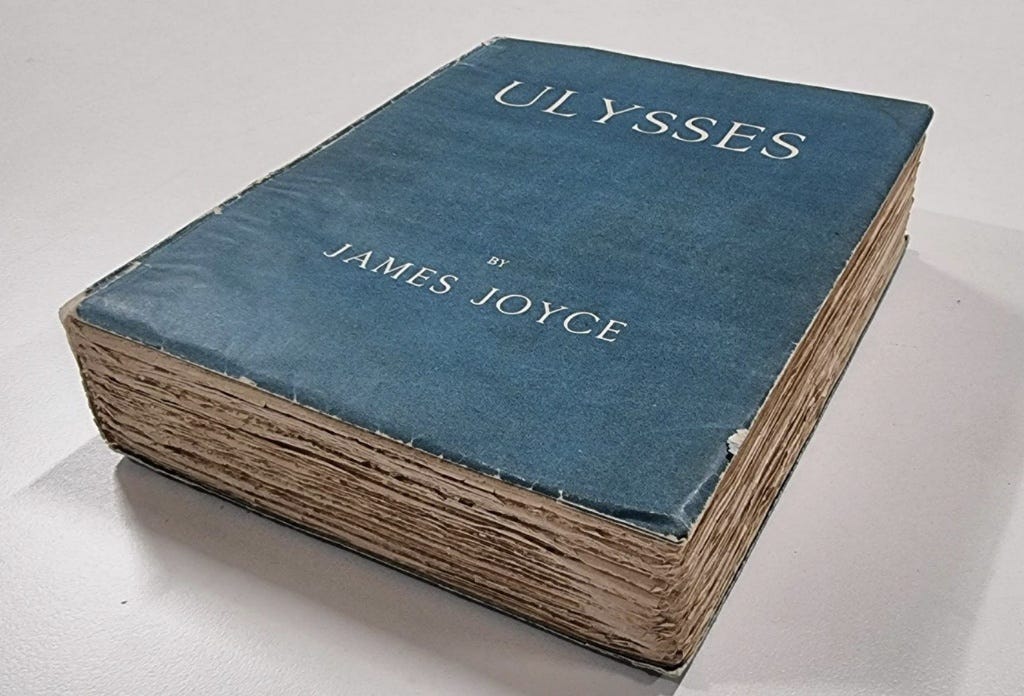

Ulysses @ 100

Photo credit: Geoffrey Barker under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

This is a big day for those of us who are fans of the writings of James Joyce — the hundredth anniversary of the publication of Ulysses. (Footnote: If you’re not of that persuasion, this might be the time to take the day off, and no one will think the worse of you for that. Normal service will be restored tomorrow.)

As Kevin Birmingham observes in his fascinating study, The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses, so much has been written about what’s exceptional within the pages of Joyce’s epic that we have lost sight of what happened to Ulysses itself. It’s a great story and Birmingham tells it well.

The book was banned as obscene, officially or unofficially, throughout most of the English-speaking world for over a decade. And the fact that it was forbidden is part of what made the novel so transformative. Ulysses, says Birmingham, “changed not only the course of literature in the century that followed, but the very definition of literature in the eyes of the law”.

Joyce wrote all of it by hand in notebooks, on loose-leaf sheets and on scraps of paper in more than a dozen apartments in Trieste, Zurich and Paris. A portion was burned in Paris while it was still only a manuscript draft, and it was convicted of obscenity in New York before it was even a book (parts of it were published in instalments by a small magazine). Joyce’s difficulties inspired Sylvia Beach, an American expatriate running a small bookstore in Paris, to publish the book when everyone else (including Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press) refused.

Government officials on both sides of the Atlantic confiscated and burned more than a thousand copies. Most of the surviving copies of the first edition came from Shakespeare & Company, Sylvia Beach’s shop, where, as one writer remembered, “Ulysses lay stacked like dynamite in a revolutionary cellar.”

Joyce was, by all accounts, an utterly exasperating man, but his contemporaries saw his genius clearly. He was perpetually broke and living on the charity of friends and supporters (while also living it up whenever he had money to burn). He also suffered from terrible bouts of iritis (a swelling of the iris), which in turn brought on bouts of acute glaucoma and often left him close to blindness, and he underwent traumatising eye-surgery without anaesthetics.

His grevious health problems and feeble eyesight, writes Birmingham,

made him heroic and pitiable, inaccessible and deeply human. The images of Joyce wearing eye patches and post surgical bandages or reading with thick spectacles and magnifying glass gave him the aura of a blind seer, a twentieth-century Homer or Milton. Illness was taking away the visible world only to give him an experience whose intensity was too deep for others to fathom. Ernest Hemingway once wrote to Joyce after his son’s fingernail lightly scratched his eye. “It hurt like hell,” Hemingway said. “For ten days I had a very little taste of how things might be with you.”

Yet he persevered. The book, Birmingham thinks,

reads like s desperate, beloved labor, a work of uncanny insight behind thick spectacles… It is the book of a man who, even in a hospital bed — even with both eyes bandaged — would reach for a notebook and trace phrases blindly with his pencil so that he could insert them into his manuscript when he could see again. It’s no wonder that Joyce’s fiction explored the interior world. Beyond his family, it was all he had.

Spot on. And there are many among us who are very glad that he persevered.

Quote of the Day

“History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

Ulysses, p. 31 (Bodley Head, 1937 edition)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Mozart | Il mio tesoro from Don Giovanni | Sung by John McCormack

Joyce had a fine singing voice and came close to winning first place in the singing competition at the 1904 Feis Ceoil, an annual celebration of Irish musical talent held in Dublin. The previous year the top prize (a year-long scholarship to study in Italy) had been won by John McCormack, who was friendly with Joyce and had advised him to enter the 1904 competition. But Joyce won only the bronze medal, possibly because he didn’t stick to the rubric: he refused to sight-read a musical score. He was as cussed as hell even then.

McCormack went on to a brilliantly successful career as a Bel canto tenor, while Joyce became a great modernist writer. It’s tantalising to think that we might not have had Ulysses if he had adhered to the rubric. But he was fascinated by music all his life — as you can see if you consult Ruth Bauerle’s amazing James Joyce Songbook, an astonishing (and vast) compendium of all the music to be found in his writings.

Long Read of the Day

Heeding James Joyce

Nice essay by Chris Hedges in Counterpoint.

One hundred years ago this week, Sylvia Beach, who ran the bookstore Shakespeare and Company on 12 rue de l’Odéon in Paris and nurtured a community of expatriate writers that included Richard Wright, T.S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, Thornton Wilder, Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, placed in the bookstore’s front window a 732-page novel she had published, “Ulysses” by James Joyce…

Read on.

Karl Jung’s letter to Joyce on finishing the novel

Dear Sir,

Your Ulysses has presented the world such an upsetting psychological problem, that repeatedly I have been called in as a supposed authority on psychological matters.

Ulysses proved to be an exceedingly hard nut and it has forced my mind not only to most unusual efforts, but also to rather extravagant peregrinations (speaking from the standpoint of a scientist). Your book as a whole has given me no end of trouble and I was brooding over it for about three years until I succeeded to put myself into it. But I must tell you that I’m profoundly grateful to yourself as well as to your gigantic opus, because I learned a great deal from it. I shall probably never be quite sure whether I did enjoy it, because it meant too much grinding of nerves and of grey matter. I also don’t know whether you will enjoy what I have written about Ulysses because I couldn’t help telling the world how much I was bored, how I grumbled, how I cursed and how I admired. The 40 pages of non stop run at the end is a string of veritable psychological peaches. I suppose the devil’s grandmother knows so much about the real psychology of a woman, I didn’t.

Well I just try to recommend my little essay to you, as an amusing attempt of a perfect stranger that went astray in the labyrinth of your Ulysses and happened to get out of it again by sheer good luck. At all events you may gather from my article what Ulysses has done to a supposedly balanced psychologist.

With the expression of my deepest appreciation, I remain, dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

C.G. Jung

The 11 things missing from Sue Gray’s report on ‘Partygate’

Nice commentary in openDemocracy.

TL;DR version: basically, everything that’s important is missing.

The only question is whether (as I mentioned yesterday) the Met’s investigation is capable of leading to criminal charges.

I always suspected that the report would be a damp squib — partly because the Westminster bubble (and its associated media obsession) was making so much of it.

Only time will tell if that hunch was correct. In the meantime, Johnson is safe until the May elections.

In trying to wriggle out of its responsibilities, Spotify is making a category mistake

The company’s CEO Daniel Ek vowed to provide greater transparency around Spotify’s content rules and said he wanted to support “expression while balancing it with the safety of our users.” And just like Facebook, Spotify will be labelling content with warnings and directing users to a Covid-19 information hub with input from scientists and world health experts.

There are two things wrong with this:

As various people have pointed out, attaching warning messages to content (dodgy or otherwise) about controversial matters effectively gives all messages equal status, and often merely boosts the bad stuff.

More importantly, by borrowing ideas from the Facebook playbook, Ek is making a category error. Spotify, as a Sarah Frier points out on Bloomberg’s Fully Charged, is not Facebook. “The objectionable content at issue comes not from a video or politician that happened to go viral, but from The Joe Rogan Experience, a podcast Spotify paid for the privilege of distributing exclusively on its service, in a licensing deal worth about $100 million”.

Moreover, as Frier goes on to observe,

Spotify executives are not shocked at the nature of Rogan’s pandemic content; the podcast deal was inked in May 2020, when Rogan was already a highly controversial figure. And critically: Spotify isn’t a user-generated content company, it’s a curator and publisher of selected media. Rogan is the cornerstone of its podcasting business.

(Emphasis added.)

It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out.

My commonplace booklet

Celebrate the publication centennial of James Joyce’s Ulysses in a two-day conference at The Huntington. Hmmm… Reading the blurb suggests that it’s above my pay grade. For example: “Joyce’s Ulysses uses Dublin as map as well as palimpsest upon which to inscribe his vision of worlds past and present. This conference will explore approaches to literary study that make clearer the verbal and nonverbal coordinates of Joyce’s literary terrain and their global expressions. Topics will range from forms of visualization (schemas, maps, charts, word indexes) to decolonization, intertexts and intermedia, mapping as metaphor and places as texts, in an effort to open up new ways of reading.”

Teenager seeks $50k from Elon Musk to delete Twitter bot tracking private jet Link And now the lad is going after the private jets of other billionaires. One’s heart bleeds for the poor dears.