Wednesday 19 July, 2023

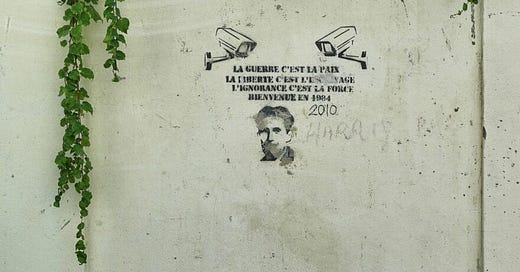

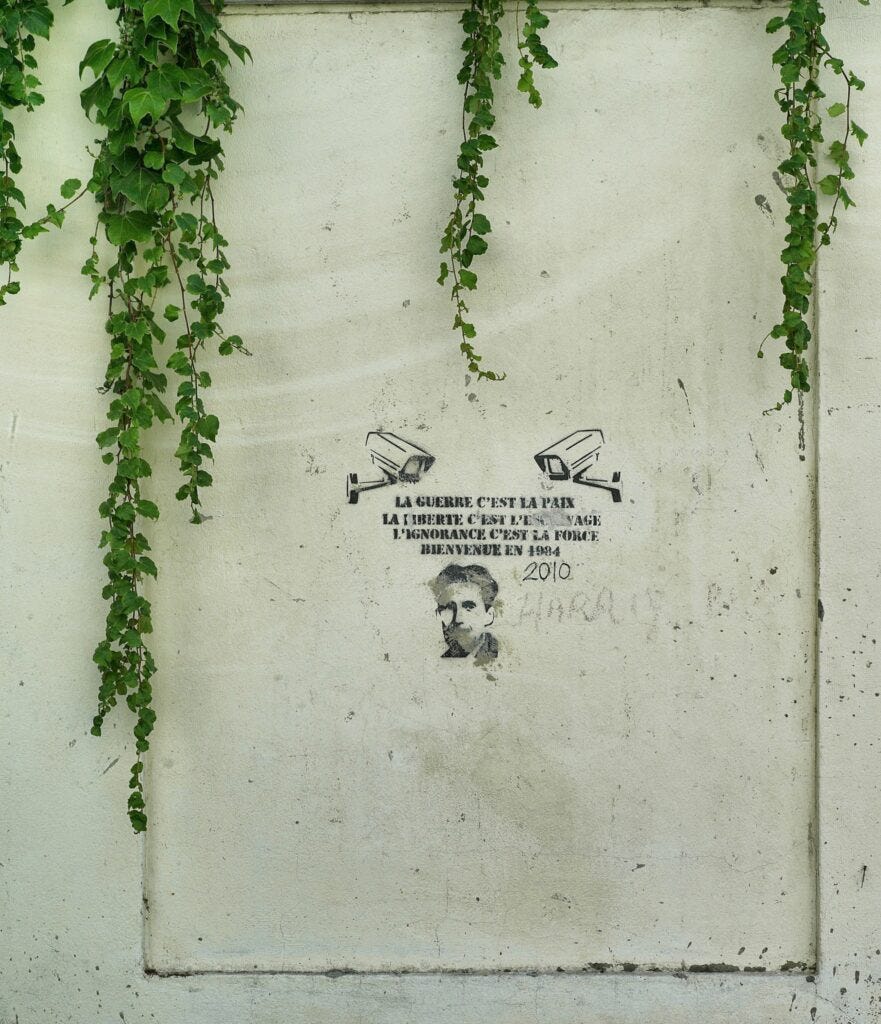

Orwell: Politics and the French Language

Arles, 2010

Quote of the Day

”’I told you so’ are the four least satisfying words in the English language.”

Bill McKibben

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Richard Wagner | Tristan und Isolde, Prelude

‘Haunting’ is one word for it. ‘Beautiful’, another.

Long Read of the Day

The New Media Goliaths

Interesting essay by the formidable Renée Diresta on how our media ecosystem has radically changed, how Chomsky’s ideas about ‘manufacturing consent’ need updating and why there is no such thing any more as ‘public opinion’ (singular)/

It’s the kind of essay that Neil Postman would have enjoyed (and about which he would have had views).

Books, etc.

Milan Kundera RIP: The Nobel Prize for Literature Winner We Never Had

The celebrated Czech novelist has died at the age of 94. Kate Webb had a nice obit of him in the Guardian. And Robin Ashenden in Quillette has a rounded assessment of him which ponders the question of why Kundera’s reputation had faded in recent decades. “You get the sense,” he writes,

that Kundera, whose novels for so long were required reading for anyone drawn to world literature, was being pushed firmly to the margins. Some of it surely was his writing on sex, which since the #MeToo movement was jarringly out of fashion. Kundera was avid about it in ways that, to the squeamish, now seemed less ground-breaking than a bit creepy, with lip-smacking descriptions of the female body and sundry deviant sex acts. But sex—which we’re no longer supposed to think or care about—represented a fraction of his themes and was arguably a legacy of the communist period, one of the few ways individuals could assert their liberty in a repressive state.

Or was it just that Kundera had become

a teller of truths inconvenient to the modern age, that his ruthless analysis of male-female relationships, his omniscient male voice and his dissection of sheep-like political movements were simply too close to the bone. More than almost any other writer, he seemed in his early work to foresee our own times: an atmosphere of growing intolerance and Rhinoceros-like groupthink that increasingly resembles the Soviet world we thought we’d left behind.

I particularly liked his Unbearable Lightness of Being and Philip Kaufman’s film of it.

My commonplace booklet

Was Napoleon Hot?

That’s the question asked by Luke Winkie in a piece in Slate triggered by the launch of the trailer for Ridley Scott’s forthcoming biopic of Boney.

Let’s get this out of the way up front: Napoleon Bonaparte was not short. Most contemporary sources put him at about 5-foot-6, typical of the average 19th-century Frenchman. He earned that apocryphal diminutive reputation from an English newspaper cartoonist named James Gillray at the dawn of the Napoleonic Wars. Gillray portrayed the emperor as a stormy, teensy-tiny toddler—flipping tables, stomping his feet—a likeness that swiftly became canonized across the world.

All of this is to say that the dimensions of Joaquin Phoenix (5-foot-8) fit neatly into a historically authentic Bonapartian silhouette, which is surely why Ridley Scott tapped him to play the leading man in the forthcoming epic Napoleon. What is less clear is whether or not Napoleon possessed the striking movie-star good looks—and almost uncanny facial symmetry—of someone like Phoenix. Scott certainly seems intent on making us think so. The first trailer for the film was released on Monday, giving us an initial taste of Joaquin in full Grande Armée regalia. I watched it over and over again, stuck on the same burning question. “Wait a minute, am I supposed to think that Napoleon was hot?”

As it happens I have a dog in this fight: I’m 5’6” and definitely not hot.

Was Boris Johnson undemocratically removed from Parliament?

In a word (well, a splendid blog post by Mark Elliott, a distinguished public law scholar), No.

Although Johnson chose to avail himself of no part of it, there is a clear and carefully constructed system for dealing with situations in which MPs are found to have engaged in certain forms of misconduct that sound either in criminal conviction or suspension from the House of Commons for a period that signals the seriousness of the wrongdoing that has been established. We can also see that this system is not undemocratic. That is so for two reasons. First, the system is rooted in both the processes of the House of Commons and in legislation enacted by Parliament, and which therefore necessarily enjoys a democratic imprimatur. Second, not only is the system underpinnedby arrangements that were put in place democratically; the system also exhibits several democratic characteristics: the Committee cannot suspend, let alone remove, an MP; suspension can occur only if supported by a majority of MPs in the House of Commons; a recall petition is subject to the requirement of the support of 10 per of voters in the MP’s constituency; and the MP is free to stand in the resulting by-election should the recall petition succeed.

That Johnson was not undemocratically or otherwise improperly ‘forced out’ of Parliament is thus an argument that can be made out quite straightforwardly and without taking any position on the egregiousness or otherwise of Johnson’s conduct — whether in terms of the acknowledged rule-breaking at the heart of Partygate or his subsequent statements to the House of Commons and the Committee of Privileges. The contrary narrative, according to which Johnson was undemocratically ejected from Parliament, is both deeply flawed and highly corrosive. Indeed, its post-truth character means that it can be described as Trumpian without any risk of hyperbole.

Yep.

Thanks to Quentin for alerting me to it.