Tuesday 24 January, 2023

Leaves of ice

It’s still cold around here.

Quote of the Day

”The people of Crete, unfortunately, make more history than they can consume locally.”

Saki (H.H. Munro)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Like Someone in Love (by Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke) | Gregory Chen (Piano), Mike Karn (Bass), Scott Lowrie (Drums)

Long Read of the Day

The Dark Underbelly of ChatGPT

Good exposé by Time.

In its quest to make ChatGPT less toxic, OpenAI used outsourced Kenyan labourers earning less than $2 per hour.

To build that safety system, OpenAI took a leaf out of the playbook of social media companies like Facebook, who had already shown it was possible to build AIs that could detect toxic language like hate speech to help remove it from their platforms. The premise was simple: feed an AI with labeled examples of violence, hate speech, and sexual abuse, and that tool could learn to detect those forms of toxicity in the wild. That detector would be built into ChatGPT to check whether it was echoing the toxicity of its training data, and filter it out before it ever reached the user. It could also help scrub toxic text from the training datasets of future AI models.

To get those labels, OpenAI sent tens of thousands of snippets of text to an outsourcing firm in Kenya, beginning in November 2021. Much of that text appeared to have been pulled from the darkest recesses of the internet. Some of it described situations in graphic detail like child sexual abuse, bestiality, murder, suicide, torture, self harm, and incest.

OpenAI’s outsourcing partner in Kenya was Sama, a San Francisco-based firm that employs workers in Kenya, Uganda and India to label data for Silicon Valley clients like Google, Meta and Microsoft. Sama markets itself as an “ethical AI” company and claims to have helped lift more than 50,000 people out of poverty.

The data labelers employed by Sama on behalf of OpenAI were paid a take-home wage of between around $1.32 and $2 per hour depending on seniority and performance. For this story, TIME reviewed hundreds of pages of internal Sama and OpenAI documents, including workers’ payslips, and interviewed four Sama employees who worked on the project. All the employees spoke on condition of anonymity out of concern for their livelihoods.

OpenAI confirmed that Sama employees in Kenya contributed to a tool it was building to detect toxic content, which was eventually built into ChatGPT.

Books, etc.

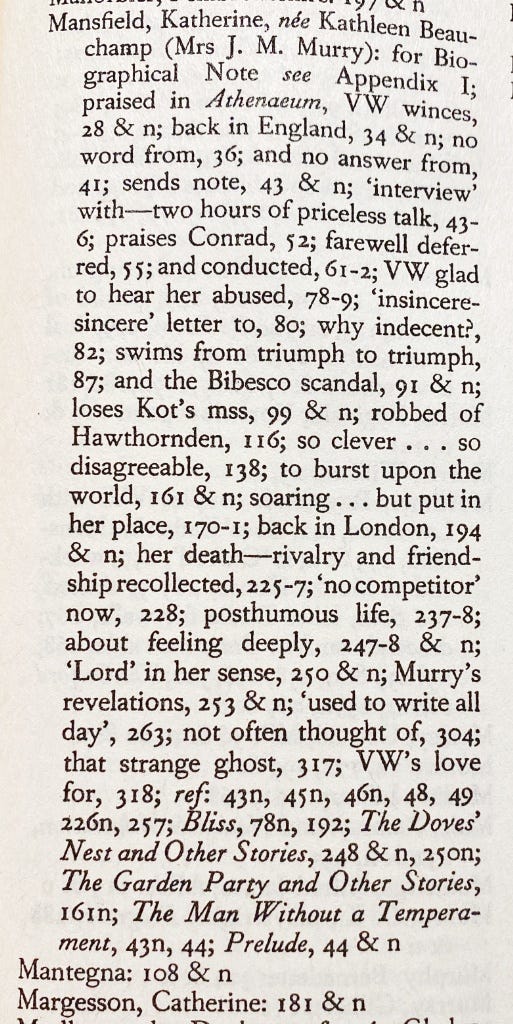

One of the things that’s always puzzled me about Virginia Woolf’s diaries (to which I am addicted) is her apparent obsession with Katherine Mansfield. Here are the index entries for her in Volume 2 of the Woolf diaries.

Although puzzled by Woolf’s obsession with KM, I’ve always put off reading her. Life’s too short, etc.

Now, however, an essay by Kirsty Gunn in Literary Hub has persuaded me that that omission will have to be rectified. This month is the centenary of KM’s death — which, says Ms Gunn,

marks the beginning of a flurry of publications and reviews honoring the author of a prose style that Virginia Woolf envied (“I was jealous of her writing,” she wrote after Mansfield’s death, “the only writing I have ever been jealous of”) and whose stories established a prototype for the kind of short fiction in English we now take for granted.

And,

Her stories plunge the reader into their midst and off we go: “And after all the weather was ideal.” “The week after was one of the busiest weeks of their lives.” “In the afternoon the chairs came.” From their first lines, the reader is brought right inside the fictional worlds which simply seem to open up and change as time passes—a method that Mansfield herself described as “unfolding,” introducing to literature a kind of free indirect narrative that traces the actions and minds of characters with such detail and nuance and sensitivity that she may as well be writing in invisible ink. “What form is it? you ask,” she wrote in a letter to the painter Dorothy Brett about her long short story “Prelude,” first published by the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press. “As far as I know it’s more or less my own invention.”

Time to visit a bookshop.

My commonplace booklet

Rentokil pilots facial recognition system as way to exterminate rats

At first I thought that this has to be a spoof released inadvertently two months ahead of April 1st. If it is, then both the Financial Times and the Guardian have taken the bait.