Saturday 15 August, 2020

Quote of the Day

“The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.”

Bertrand Russell

Musical alternative to the morning’s news

Jessye Norman: Mozart – Le Nozze di Figaro, ‘Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro’

The significance of the Twitter hack

Damn! This great piece by Bruce Schneier was published on July 18 and I missed it. Growl.

Still, better late than never…

Twitter was hacked this week. Not a few people’s Twitter accounts, but all of Twitter. Someone compromised the entire Twitter network, probably by stealing the log-in credentials of one of Twitter’s system administrators. Those are the people trusted to ensure that Twitter functions smoothly.

The hacker used that access to send tweets from a variety of popular and trusted accounts, including those of Joe Biden, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk, as part of a mundane scam—stealing bitcoin—but it’s easy to envision more nefarious scenarios. Imagine a government using this sort of attack against another government, coordinating a series of fake tweets from hundreds of politicians and other public figures the day before a major election, to affect the outcome. Or to escalate an international dispute. Done well, it would be devastating.

en passant, the US is heading for an election that will not be decided on the day, but after a period (of unknown duration) while postal votes are being counted (and maybe argued over). Another Twitter hack on the lines just suggested could be catastrophic.

So here’s the nub of it:

Internet communications platforms—such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—are crucial in today’s society. They’re how we communicate with one another. They’re how our elected leaders communicate with us. They are essential infrastructure. Yet they are run by for-profit companies with little government oversight. This is simply no longer sustainable. Twitter and companies like it are essential to our national dialogue, to our economy, and to our democracy. We need to start treating them that way, and that means both requiring them to do a better job on security and breaking them up.

Google’s Advertising Platform Is Blocking Articles About Racism

This is both shocking — and unsurprising:

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day this year, the Atlantic decided to recirculate King’s famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” which the magazine had run in its August 1963 issue and republished, in print and online, in 2018. Several hours later, the publication’s staff noticed that Google’s Ad Exchange platform, which serves many of the ads on the Atlantic’s website, had “demonetized” the page containing the letter under its “dangerous or derogatory content” policy. In other words: As part of its efforts to protect advertisers from offensive internet content with which they would not want their products to be associated, Ad Exchange had locked out one of the most important texts of the civil rights movement.

Google controls more than 30 percent of the digital ads market. A big chunk of that business happens through Ad Exchange, a marketplace for buying and selling advertising space across the web. According to its publisher policies, Google does not monetize, or allow advertising on, “dangerous or derogatory content” that disparages people on the basis of a characteristic that is associated with systemic discrimination—race, gender, sexual orientation, disability, etc. As the policy outlines, this might look like “promoting hate groups” or “encouraging others to believe that a person or group is inhuman.” Because of the scale of Google’s ad-serving business, however, it can’t enforce this policy on the front lines by hand, so instead the company uses an algorithm that, in part, scans for offensive keywords in articles. But the system doesn’t always take context into consideration. Several mainstream publishers, including Slate, have had articles demonetized under this policy when covering race and LGBTQ issues.

Automated ‘moderation’ is context-blind, in other words. It’s just another confirmation that these companies can’t fulfil their moral and ethical obligations at the scale on which they operate, given the business models on which they depend.

US Postal Service warns 46 states their voters could be disenfranchised by delayed mail-in ballots

This is paywalled on the Washington Post site, but here is the gist:

Anticipating an avalanche of absentee ballots, the U.S. Postal Service recently sent detailed letters to 46 states and D.C. warning that it cannot guarantee all ballots cast by mail for the November election will arrive in time to be counted — adding another layer of uncertainty ahead of the high-stakes presidential contest.

The letters sketch a grim possibility for the tens of millions of Americans eligible for a mail-in ballot this fall: Even if people follow all of their state’s election rules, the pace of Postal Service delivery may disqualify their votes.

The Postal Service’s warnings of potential disenfranchisement came as the agency undergoes a sweeping organizational and policy overhaul amid dire financial conditions. Cost-cutting moves have already delayed mail delivery by as much as a week in some places, and a new decision to decommission 10 percent of the Postal Service’s sorting machines sparked widespread concern the slowdowns will only worsen. Rank-and-file postal workers say the move is ill-timed and could sharply diminish the speedy processing of flat mail, including letters and ballots.

My immediate thought was that this is linked to the appointment of a Trump stooge as the Postmaster-General. But apparently it pre-dates his appointment:

The ballot warnings, issued at the end of July from Thomas J. Marshall, general counsel and executive vice president of the Postal Service, and obtained through a records request by The Washington Post, were planned before the appointment of Louis DeJoy, a former logistics executive and ally of President Trump, as postmaster general in early summer. They go beyond the traditional coordination between the Postal Service and election officials, drafted as fears surrounding the coronavirus pandemic triggered an unprecedented and sudden shift to mail-in voting.

Everywhere one looks, norms and conventions that we took for granted in liberal democracies are wilting or being undermined. The chances of the US having an uncontested election result diminish by the day.

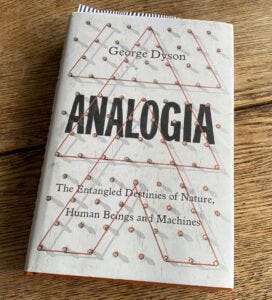

Summer books #4

Analogia: The Entangled Destinies of Nature, Human Beings and Machines by George Dyson, Allen Lane, 2020.

I’m exactly half-way through this extraordinary book, and I still don’t know where it’s headed. But it’s an infuriatingly compelling read. George Dyson is an extraordinary member of an extraordinary family — the son of the theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson and mathematician Verena Huber-Dyson, the brother of technology analyst Esther Dyson, and the grandson of the British composer Sir George Dyson. He has led an amazing life as a roving explorer, craftsman and public intellectual. Having being brought up in Princeton, where his father was an academic in the Institute for Advanced Study, he dropped out of a couple of universities before heading for the West Coast of Canada. From 1972 to 1975, he lived in a tree-house at a height of 30 metres that he built from salvaged materials on the shore of Burrard Inlet in British Columbia. He became a Canadian citizen and spent 20 years in that part of the world designing kayaks, researching historic voyages and native peoples, and exploring the Inside Passage.

In recent decades he’s become interested in the history of computing and the direction of travel of our increasingly digitized world. Everything he’s written on these subjects interweaves his own personal history with polymathic knowledge of all kinds of subjects and speculations on what it all means for the future. This, his latest book, follows the same pattern. Where he’s heading, I suspect, is towards the conclusion that, in the end, the digital will run out of steam, and we’ll discover that analog computing (which after all is what goes on in our brains) will have the last laugh. As someone who started on analog computers before moving to digital devices I’m intrigued to see if that hunch is correct. But there’s another 150 pages to go and anything may happen: you never can tell with the Dysons. After all, George’s father devoted a couple of years of his life to a US-funded project to build a huge spaceship powered by nuclear explosions and was mightily pissed off when the US instead opted for Werner von Braun and his primitive, chemical-fuelled, rockets.