Monday 31 October, 2022

The disappearance of childhood

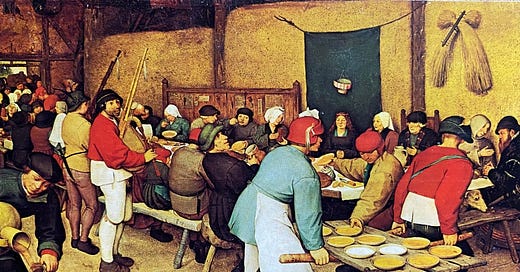

Coming on this picture by Breugel, The Peasant’s Wedding, when rummaging through a collection of postcards yesterday made me dig out and re-read Neil Postman’s wonderful book, The Disappearance of Childhood, in which he argued that our conceptions of childhood are shaped by the dominant communications technology of our age.

In the oral culture of the pre-Gutenberg age, he says, childhood ended when a young person could competently communicate — which in the Middle Ages was judged to be seven years of age. This is why the Catholic Church declared seven to be the “age of reason” (and the age at which children growing up, like me, in 1950s Ireland made their First Communion). It’s also why, Postman argued, you never see children in Breugel paintings — you just see small people dressed in adult garb.

As J.H. Plumb put it,

“There was no separate world of childhood. Children shared the same games with adults, the same toys, the same fairy stories. They lived their lives together, never apart. The coarse village festival depicted by Breughel, showing men and women besotted with drink, groping for each other with unbridled lust, have children eating and drinking with the adults”.

Postman’s argument was that the rise of a print (i.e. literate) culture lengthened the conception of childhood (to the age of 12, perhaps), because it took longer to achieve communicative competency in such a culture. He went on, famously, to argue that the dominance of broadcast television from the mid-1950s had reduced the period of childhood to about three years, because above that age children could follow most of what what was being shown on US television!

Quote of the Day

”Never did I read such tosh.”

Virginia Woolf on Joyce’s Ulysses, in a letter to Lytton Strachey, 24 April, 1922

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

The SteelDrivers | Blue Side Of The Mountain

Long Read of the Day

Into the muck

An interesting review essay by Noam Maggor on the French economist Thomas Piketty’s three books, triggered (I’d guess) by the recent publication of a collection of the his newspaper columns (which I never see because they’re in French). The piece provides a useful Cook’s tour of Piketty’s intellectual journey — starting with his pioneering, data-intensive study of the way in which the imbalance between wages and return on capital in the US and Europe over the last 200 years varied, and the presentation of his ‘iron law’ expressed as r > g, where r is the return on capital and g is the rate of economic growth. Missing from his chronicle, though, was any explanation for how this relationship came to be so solid.

In the end, Piketty came to the conclusion that the explanation lay not in economics but in with ideology, which is why the title of his sprawling second book, Capital and Ideology, gives the game away: inequality is a product of politics.

Or, as Maggor puts it:

Inequality did not simply emerge from economic reality, from technological change or the organization of production, nor from inherent disparities in individual talent, ability, or effort. Rather, inequality is determined through struggles that take place in the political sphere. These struggles dictate the terms of engagement in the market and, by extension, the market’s distributional outcomes. Why do some groups in society accumulate wealth over time? Not because they are more deserving in any objective-economic or natural-Darwinian sense – but because they were able to write the political rules in ways that have benefited them at the expense of others.

I haven’t read Capital and Ideology so found this essay useful. Hope you do too.

And while you’re at it, it’d be worth looking at 15 proposals on what to do about inequality by the late, lamented Tony Atkinson who was the great scholar of inequality.

LinkedIn has a fake profile problem – can it fix this blot on its CV?

Yesterday’s Observer column:

Once upon a time, when LinkedIn was the newest new thing, the standard response to anyone who proudly announced that they were “now on LinkedIn” was: “Oh! I didn’t know you were looking for a job.” But then, as always happens with digital stuff, what was once new became routine and, eventually, de rigueur.

I first realised this when my Cambridge college put on an event for students who aspired to become entrepreneurs and we organised a day during which each student could have a conversation with a local venture capitalist or tech investor. I sat in on some of the conversations and was astonished to find that one of the first questions the mentors asked was: “Are you on LinkedIn?” Students who were not were firmly advised to fix that, pronto.

Intrigued, I signed up and was invited to “make the most of your professional life”. I noted that by clicking on “Agree & Join” I was accepting not only the LinkedIn user agreement but also the company’s privacy policy and cookie policy, which indicated that this was just another surveillance capitalist masquerading as a service. But since I have always tried not to write about stuff that I don’t use, I clicked. I then found that I could do interesting things such as uploading my (non-existent) CV, providing details of my “career”, interests, etc, after which I sat back to see what happened.

What happened was, essentially, spam – in the form of unsolicited messages and invitations from LinkedIn…