A winter seascape

I love this picture by John Darch (Whom God Preserve) taken the other day on the beach at Ballybunion in Kerry. It’s a beach I knew well as a child, because my father (a keen golfer) was a member of the golf club there and the rest of the family sometimes decamped to the beach while he and his three regular playing partners tackled the fairways, rough, bunkers and greens of what the great Tom Watson (who won five British Opens) once called “the best golf course in the world”.

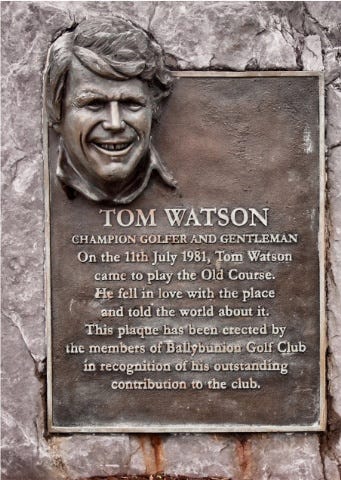

Later on, members of the club commissioned this plaque in his honour.

Quote of the Day

”I think this is what’s wrong with our political system. It’s organized to get people elected, then the people we elect do the work of big companies. And their work is to squeeze every bit of value they can out of the natural and intellectual resources of the world, and keep it for themselves. If they can kill something that’s worth $100 to reap $1 of value from the corpse, they see that as good business. That’s the approach that has got our species into the climate change corner we’re in. If you burn everything all you’ll have left to breathe are smoking corpses. That’s where we are in everything humans do. That’s why we feel a void for ourselves, collectively. We blame the government, but we’re the ones who believe the lies. We know they’re lying but we believe them anyway.

Dave Winer, as part of a blog post explaining why he was so disappointed by Obama’s Presidency, despite having supported him in every way he could.

Seemed like an appropriate quotation to start the year.

Musical alternative to the radio news of the Day

Mozart | 12 Variations on Ah, vous dirai-je, maman KV 265 | Clara Haskil

Such a show-off, that Mozart kid. The piece reminds me of the film Amadeus and Peter Shaffer’s portrayal of him as “the John McEnroe of music” (as some critic put it.)

Long Read of the Day

Greta Thunberg ends year with one of the greatest tweets in history

Lovely piece by Rebecca Solnit on the connection between machismo, misogyny and hostility to climate action.

On 27 December, former kickboxer, professional misogynist and online entrepreneur Andrew Tate, 36, sent a boastfully hostile tweet to climate activist Greta Thunberg, 19, about his sports car collection. “Please provide your email address so I can send a complete list of my car collection and their respective enormous emissions,” he wrote. He was probably hoping to enhance his status by mocking her climate commitment. Instead, she burned the macho guy to a crisp in nine words.

Cars are routinely tokens of virility and status for men, and the image accompanying his tweet of him pumping gas into one of his vehicles, coupled with his claims about their “enormous emissions”, had unsolicited dick pic energy. Thunberg seemed aware of that when she replied: “yes, please do enlighten me. email me at smalldickenergy@getalife.com.”

Her reply gained traction to quickly become one of the top 10 tweets of all time…

Read on. It’s a great story.

Books, etc.

As an experiment, we’re reading E.M.Forster’s novels and then watching the movies that have been based on them. We started with Room with a View, and then moved on to Howards End. A Passage to India is obviously the next on the list, but Christmas intervened, so that one is for 2023.

It’s been an interesting journey. First of all, it’s nice to re-engage with the books and to observe Forster’s writerly strengths and foibles; but most importantly to appreciate their significance in the era when they were first published. On that last criterion, he comes out of it well, tackling issues (sexism, imperialism, misogyny, class, sexuality) that were mostly taboo in his time.

It’s also interesting to see how screenwriters and directors like the Merchant Ivory team take a story one has come to know well and tell it in a different medium. Sometimes the book does it better; sometimes vice versa. And occasionally the film has to fill in gaps that the novelist has glossed over. In Howard’s End, for example Leonard Bast’s heart disease is not mentioned in the novel until after his violent death, whereas Merchant Ivory go to some lengths to set it up in the film.

I have a soft spot for Forster because — in one of those serendipitous accidents that shape a life — I attended his 90th birthday party. I was there because one of the first things my late wife Carol and I did when we arrived in Cambridge in 1968 was to join the Cambridge Humanists, of which he was then the Patron. The society decided to celebrate his birthday in his rooms in King’s and all members were invited. And there he was, in a wheelchair, but very much present. What struck me was how small and modest he looked: there was nothing of the ‘great man of literature’ about him. Which was reassuring but also slightly disappointing to an impressionable lad like me.

The event was hosted by Francis Crick, who six years earlier had (with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins) won the Nobel prize for the discovery of the molecular structure of DNA.

As you can imagine, it was a heady experience for a scholarship boy (and an engineering student) who had just arrived from Ireland. Afterwards I read several of Forster’s novels followed by Aspects of E.M. Forster, a nice collection of essays by friends of his which had been given to me by John Fenton (also a member of the Cambridge Humanists). I’ve just re-read it with renewed pleasure, and re-learned things from it (such as how Forster had wound up as a Fellow of King’s) that I had forgotten.

But the book of Forster’s that I liked best was his collection of essays, Two Cheers for Democracy which somehow better evoked the quiet, undemonstrative, uncharismatic liberal I had seen on his birthday.

I’ve always liked his adage that “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.” And Two Cheers is full of evocations of that quiet, undemonstrative, liberal temperament of his. Think of, “I do not believe in Belief… Lord, I disbelieve — help thou my unbelief.” Or, “Think before you speak is criticism’s motto; speak before you think creation’s.” Or, “The only books that influence us are those for which we are ready, and which have gone a little further down our particular path than we have yet got ourselves.”

My one quibble with Forster is that he was wrong about Joyce’s Ulysses, which — in Chapter 6 of Aspects of the Novel — he described as

a dogged attempt to cover the universe with mud, an inverted Victorianism, an attempt to make crossness and dirt succeed where sweetness and light failed, a simplification of the human character in the Interests of Hell.

But then even Virginia Woolf got Ulysses wrong, so Forster was in good company.

My commonplace booklet

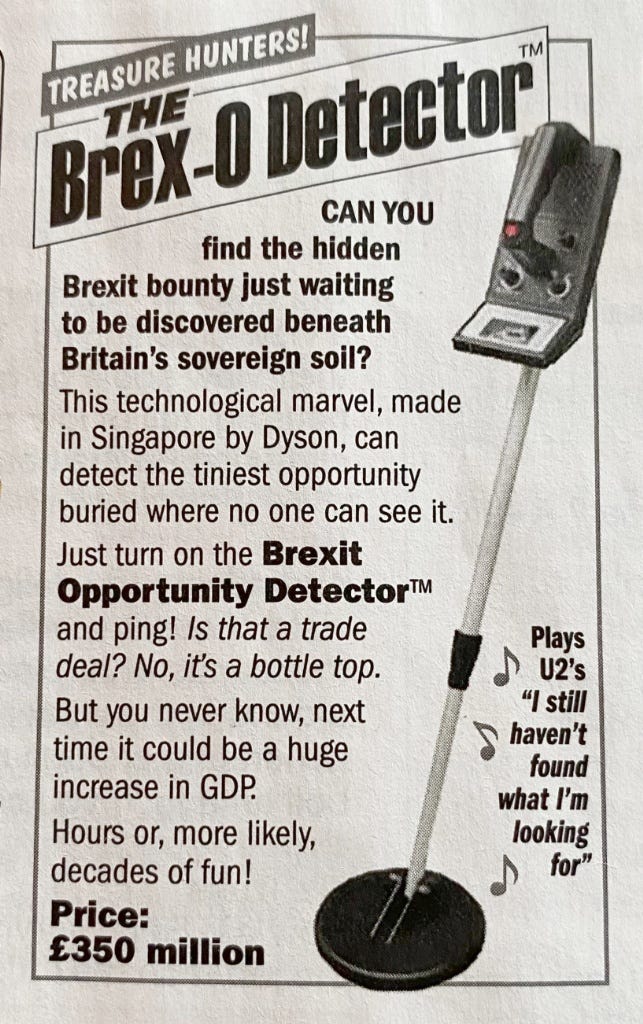

For the Brexiteer in your life

God Save Private Eye!