Remembering Z

Two years ago we said our goodbyes to Zoombini, the most remarkable cat I’ve ever known. She was a deeply intelligent creature with a need for human contact which was sometimes almost eerie. When we sat down for breakfast every morning, she would come from wherever she had been in the house and stand looking up at us in wide-eyed astonishment. The clear message was: why am I not in on this? In the end we caved in and set up a high stool between us on which she would sit or stand alertly watching proceedings. It was as if she felt she had a right to be in on all our deliberations, including the cryptic crossword we do most mornings.

When she died we had a proper family wake for her in the garden, complete with drinks and stories about her many adventures. So she was given a proper sendoff and is buried in a corner of the garden that she had made her own. But we miss her, even now.

Her sister lives on and is now 19 pushing 20, and in reasonably good shape. She’s lovely in her way, but is a completely different presence in the house.

Quote of the Day

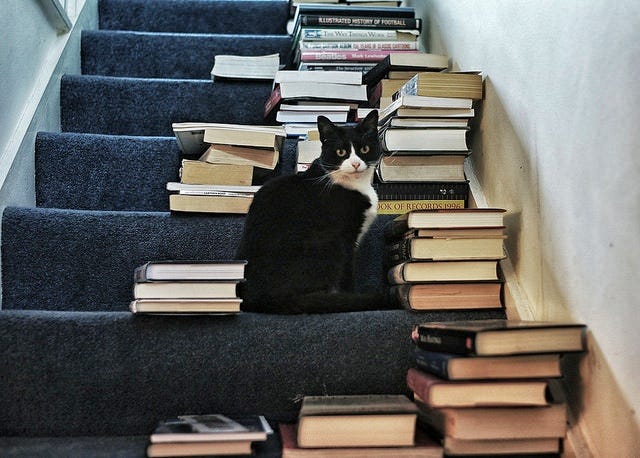

“You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.”

Ray Bradbury

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Ashokan Farewell | Jay Ungar & the Molly Mason Family Band.

Jay Ungar’s beautiful, haunting tune was made world-famous by Ken Burns’s memorable Civil War documentary series, which led me to assume that it was a tune composed during the Civil War. But no, it was composed by Jay Ungar in 1982, and since then everyone and his dog (including, would you believe, the Royal Marines Band) has recorded cover versions. But this one, featuring the composer and his friends, is the one I like best.

Jay and Molly Mason are amazing musicians. During the pandemic the Library of Congress asked them to do a concert from home. Which they did — and the recording is terrific. It’s nearly 40 minutes long, so you might need to brew some coffee and cancel your next appointment.

Long Read of the Day

What if We’re Thinking About Inflation All Wrong?

Terrific New Yorker article by Zachary Carter (who wrote an interesting book a while back on Keynes and Keynesianism) about what happened to Isabella Weber, an economist who wrote a thoughtful article in the Guardian suggesting that price controls might be an effective way of clamping down on the rampant price-gouging that’s gone on in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Cancelling Christmas was, of course, a disaster. Raised in West Germany during the reunification era, Isabella Weber had been working as an economist in either Britain or the United States for the better part of a decade. An annual winter flight back to Europe was the most important remaining link to her German friends and family. But in December, 2021, the Omicron variant was surging, and transcontinental travel felt too risky. Weber and her husband drove from the academic enclave of Amherst, Massachusetts, to a pandemic-vacated bed-and-breakfast in the Adirondacks, hoping to make the best of a sad situation. Maybe Weber could finally learn how to ski.

Instead, without warning, her career began to implode. Just before New Year’s Eve, while Weber was on the bunny slopes, a short article on inflation that she’d written for the Guardian inexplicably went viral. A business-school professor called it “the worst” take of the year. Random Bitcoin guys called her “stupid.” The Nobel laureate Paul Krugman called her “truly stupid.” Conservatives at Fox News, Commentary, and National Review piled on, declaring Weber’s idea “perverse,” “fundamentally unsound,” and “certainly wrong.”

“It was straight-out awful,” she told me. “It’s difficult to describe as anything other than that.”

Guess what? The point of Weber’s Guardian piece had been that if price-controls were the way the US economy got through the Second World War without runaway inflation, might not those ideas have a contemporary relevance. But it turned out that however disdainful Nobel Laureates like Krugman were, governments outside of the US were very interested in her ideas, and became even more so after Russia invaded Ukraine and the world found itself with a real war on its hands. Krugman eventually apologised, but he ought to have been ashamed of himself.

Carter tells the story well, but he doesn’t address two questions that struck me about it.

weren’t there overtones of crude male sexism in the disdain of the economists who attacked her for having the temerity to suggest a radical idea?

doesn’t the whole story demonstrate how an academic discipline’s slavery to its conventional wisdom — its reigning paradigm in Kuhnian terms — makes it collectively stupid?

Or, to put it more crudely: an ideology is what determines how you think when you don’t know you’re thinking.

Anyway, the piece is worth your time.

China and physics may soon shatter our dreams of endless computing power

My column in yesterday’s Observer:

This ability to cram more and more transistors into a finite space is what gave us Moore’s law – the observation that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit will double every two years or so – and with it the fact that computer power has been doubling every two years for as long as most of us can remember. The story of how this happened is a riveting tale of engineering and manufacturing brilliance and is brilliantly told by Chris Miller in his bestselling book Chip War, which should be required reading for all Tory ministers who fantasise about making “Global Britain” a tech superpower.

But with that long run of technological progress came complacency and hubris. We got to the point of thinking that if all that was needed to solve a pressing problem was more computing power, then we could consider it solved; not today, perhaps, but certainly tomorrow.

There are at least three things wrong with this…

Do read the whole piece

Chart of the Day

The tech commentariat has been scathing about the $3,500 cost of Apple’s new gadget. But actually it isn’t all that expensive by historical standards. It is pricier than the iPhone was when it launched; but it’s significantly less expensive than an IBM PC was in 1981, or the Compaq ‘portable’ after which I lusted in 1983.

h/t to Azeem Azhar.