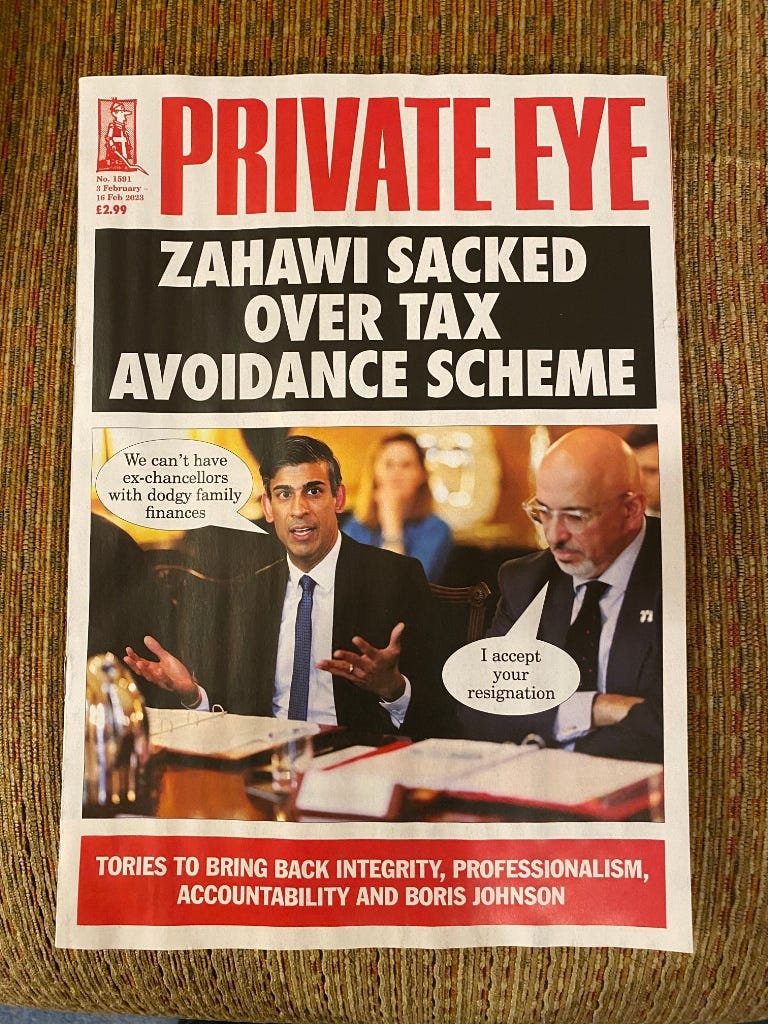

Double jeopardy

The current cover of Private Eye! Worth buying this week.

Quote of the Day

“Nature still obstinately refuses to co-operate by making the rich people innately superior to the poor people.”

Beatrice Webb

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Abide With Me | Choir of King’s College, Cambridge

I’m going to a friend’s funeral today, and hoping this will be one of the hymns.

Long Read of the Day

The End of the Intellectual Focal Point

A perceptive essay by Daniel Drezner on the way a particular sector of the public sphere — that occupied by ‘public intellectuals’ — is changing.

One of the key themes from The Ideas Industry was that the barriers to entry for entering the marketplace of ideas had been lowered. Traditional gatekeepers — like, say, the op-ed editors of the New York Times or Washington Post — exercised less power than they used to. It has become easier for a thought leader to bypass establishment venues and essentially engage in the intellectual equivalent of direct marketing.

That said, the dramatic shifts in the social media landscape over the past six months should remind everyone that the relationship between traditional gatekeepers and thought leaders might be a bit more complicated. Thought leaders might not want to be constrained by establishments, but they do want to be talked about by establishments. They like long profiles about their intellectual arc or consideration of just how transgressive their ideas really are. Indeed, antagonizing the establishment is a surefire means of building a brand for a lot of thought leaders.

What if, however, there is no longer an establishment to push against?

Also has interesting things to say about the role of Twitter in the public sphere.

Shelling out

Timely observation by Jonty Bloom:

Shell is making obscene profits while the country spends billions subsiding energy bills. The company reported its largest ever profits and quite possible the highest profits of any British company ever, $40bn.

The year before it made $19bn and since it has not bought any other firms, expanded its business significantly or invented a new form of energy; this is just a windfall gain from higher energy prices.

The moral and economically sensible thing is to tax this gain, all of it. The problem is not that this would restrict investment or is unfair, it isn’t. The problem is that the government is so insanely free market that it sees nothing wrong with unearned profits.

That’s ideology at work. Interestingly, although Margaret Thatcher was, in a way, a neoliberal, she had no objection to windfall profits.

Books, etc.

On novels and the movies they inspire

I’ve recently watched two movies about episodes in the lives of two writers I admire — Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. Vita and Virginia is about the passionate affair that Woolf had with Vita Sackville-West and the way that led to her path-breaking novel Orlando. Nora is about the relationship between James Joyce and his long-suffering wife, Nora — but told from Nora’s point of view. It’s based on Brenda Maddox’s fine biography of Nora and shows how Joyce drew on that tempestuous relationship in his fiction – especially Dubliners and Ulysses.

I read Orlando many years ago and — to be honest — remember little about it except that I didn’t enjoy it much. And I was therefore puzzled by the fact that it seemed to be widely regarded as Woolf’s greatest literary achievement. It tells the story of an English poet who changes sex and lives for centuries, meeting the key figures in literacy history. In the process Woolf manages not only to raise transgender issues which (coincidentally) have startling contemporary resonances, but also to satirise the misogyny of conventional historical narratives, imperialist ideology and Victorian complacency.

All of this passed me by when I first read the novel, and reading the terrific Wikipedia entry on it has therefore been an embarrassing experience, not to mention a reminder of youthful ignorance and naivete! But the great — and unexpected — benefit of watching the movie was that I suddenly began to see how Woolf’s infatuation with her aristocratic bisexual lover provided the spur for her exploration of really momentous themes in her novel. As the man said, you learn something every day!

I’m not a movie buff – and indeed generally watch very few films – so this recent mini-binge was prompted originally by curiosity about how novels are adapted for the screen. In relation to Joyce, the great breakthrough was Brenda Maddox’s biography of Nora, because it vapourised the conventional narrative about the uneducated wife who never read the works of the genius to whom she was married. How she endured it was — according to the narrative — a mystery, for Joyce, in addition to being a genius, was also an impossible person to live with.

This patronising view of Nora was encapsulated in something Richard Ellmann — Joyce’s canonical biographer — wrote to Maddox when she was embarking on her quest saying how much he disliked “book-length studies of people who are clearly not of great importance themselves”. He added that Nora’s meagre correspondence and literary output would make it “possible neither to give a full character portrayal, nor to evolve a feminist tract” about her.

Maddox’s genius was to spot that what Joyce was looking for was “a Catholic girl without a Catholic conscience” — and, boy, did he find one!

I knew Maddox when I was the Observer’s TV critic and she was a prominent and influential media figure, and I liked her a lot. I found her a shrewd and detached observer of that strange world whose products I reviewed.

In the movie this interpretation of Nora is beautifully captured by Susan Lynch, and Joyce as the impossible-to-live-with genius is also well portrayed by Ewan McGregor. The adaptation shrewdly opted to cover just the pre-Ulysses period of their life together — up to the point where it was clear that Dubliners would never be published in Ireland, and that they would never return to live there.

That decision gave it a coherence that it would have lacked if the film had tried to cover the entire course of Mr and Mrs Joyce’s life together. And what it vividly illustrated were the myriad ways in which life with Nora shaped Joyce’s imagination and found expression in his fiction. We finally discover, for example, where the wonderful closing moments of ‘The Dead’, his little masterpiece, came from: Nora’s relationship with a young boy in Galway who had died of pneumonia. And Joyce’s fantasies about Nora’s suspected infidelity provided the engine for the cuckolding of Leopold Bloom in Ulysses. Molly Bloom is, in essence, a projection of Joyce’s paranoia.

My only quibble is the way these movies about great literary figures of the past always over-glamourise them. The sets, dresses and hats are invariably over the top. The Woolfs’ Richmond house was nothing like as grand as it appears in the film. And although Joyce was a dandy and Nora a fine handsome woman, she rarely dressed like an escapee from a Paris catwalk; and at times in Trieste they lived in pretty modest conditions. Growl.

My commonplace booklet

U.S. Marines Outsmart AI Security Cameras by Hiding in a Cardboard Box

Lovely story on PetaPixel about the fragility (nay, stupidity) of image recognition systems.