Dish of the Day: Humble Pie

The caption on yesterday’s photograph from our window in the Lake District ended with the sentence “That’s Lake Windermere in the distance”.

This prompted a lovely note from James Cridland.

As my late grandmother would have sharply reminded you, the “mere” in Windermere means lake, and therefore the body of water is Windermere: never “Lake Windermere”. She lived close by for most of her life, after a career that included code-breaking in the war (both in Bletchley Park and Egypt). Every morning was spent in her conservatory, watching the river in Staveley go by, doing the cryptic crossword from The Times. The other thing she was keen on was telling people off if they said they were going to “ring up for a chat”. She, correctly, pointed out that the “up” was superfluous.

I have dispatched an ethereal apology to the lady in question, and ordered up a dish of the blogger’s customary meal.

Quote of the Day

“I work for a government I despise for ends I think criminal.”

John Maynard Keynes, 1917, in a letter to Duncan Grant

I wonder how many current Treasury officials think the same about the current Administration.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Eric Clapton and B.B. King | Worried Life Blues

Long Read of the Day

How Memes Led to an Insurrection

An interesting introduction to the role that memes now play in our political and democratic life. An excerpt from a new book by Joan Donovan, Emily Dreyfuss, and Brian Friedberg.

“We’re storming the Capitol! It’s a revolution!” a woman who identified herself only as Elizabeth from Knoxville, Tennessee, told a reporter outside the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. She had a blue Trump flag slung across her neck like a cape. Police had just maced her in the face, she recounted through tears.

As soon as this video of Elizabeth hit Twitter, it went viral. The insurrection she’d taken part in, a very real and coordinated attempt to thwart the democratic process, was also a surreal spectacle—millions watched the chaos unfold in real time on broadcast TV and on social media—and Elizabeth was one of the minor characters. On Twitter and TikTok, she became fodder for internet jokes. People remixed the video with Auto-Tune. Sleuths spun conspiracy theories: Maybe Elizabeth was a liar who hadn’t really been maced. Maybe the insurrection was a hoax. Content was crafted to fit different political orientations and different platforms, and to delight or offend different audiences.

Elizabeth had been ‘memed’. And one of the significant things about Trump was that he was the first major US politician with an instinctive understanding of how to coin and exploit memes. After all #StopTheSteal was a memetic slogan. And so, of course, was #MeToo.

But social media did not create culture wars. Instead, we’ve found, social media did to culture wars what spinach did to Popeye—it juiced them up. Suddenly you didn’t need a radio show to get your idea to millions of people. You just needed a viral tweet, or to figure out the desires of a Facebook algorithm programmed to boost outrageous and emotionally stirring content. With the scale and ease of social media, culture warriors from across the country and globe were able to find one another and gather in communal spaces where their ideas could grow.

Great essay. Worth your time.

My commonplace booklet

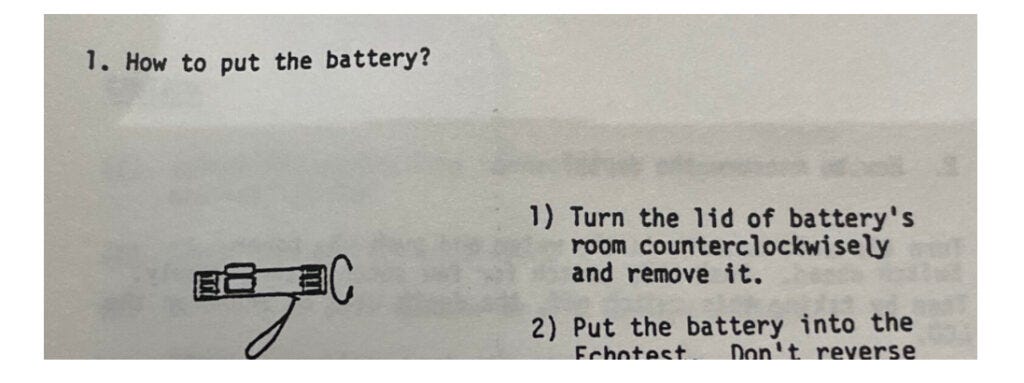

From Quentin’s blog.

“If counterclockwisely isn’t a word”, he writes, “I think it should be”.

Me too.