Friday 12 June, 2020

Edward Hopper

Hopper’s Cape Cod Morning.

There’s a marvellous piece, “Edward Hopper and American Solitude”, by Peter Schjeldahl in the New Yorker , based on an exhibition of Edward Hopper’s landscape painting currently on show in the Beyeler Foundation, Switzerland’s premier museum of modern art, outside Basel. “Though termed a realist”, Schjeldahl writes,

Hopper is more properly a Symbolist, investing objective appearance with clenched, melancholy subjectivity. He was an able draftsman and masterly as a painter of light and shadow, but he ruthlessly subordinated aesthetic pleasure to the compacted description—as dense as uranium—of things that answered to his feelings without exposing them. Nearly every house that he painted strikes me as a self-portrait, with brooding windows and almost never a visible or, should one be indicated, inviting door. If his pictures sometimes seem awkwardly forced, that’s not a flaw; it’s a guarantee that he has pushed the communicative capacities of painting to their limits, then a little bit beyond. He leaves us alone with our own solitude, taking our breath away and not giving it back. Regarding his human subjects as “lonely” evades their truth. We might freak out if we had to be those people, but—look!—they’re doing O.K., however grim their lot. Think of Samuel Beckett’s famous tag “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.” Now delete the first sentence. With Hopper, the going-on is not a choice.

Lovely. I wish I could see the exhibition. The Gallery website has a few of the pictures online

Imagine hearing this in your living room

Norah Jones has been giving concerts from her living room on YouTube. This is an excerpt from one of them. They’re absolutely entrancing, and I only learned about them by chance from a piece by Paul Elie in the New Yorker.

She has been writing new songs in response to the present. “My six-year-old has been waking up in the middle of the night for three months now, and I walk him back to his room and sit and wait for him to fall back asleep,” she told me. “I try not to look at my phone in the dead of night, but I was reading about all the things that are happening. A song will come to you, sometimes, and one came to me.” She played it right after the Ellington piece in last week’s show. It’s a cross between a street scene and a lullaby, focussed on the need to “love, listen, and learn.” Unidentified on YouTube, it sounded like a standard that Nina Simone might have sung — the sound of an artist trying to keep it together in a time of protest.

Unmissable. This is the kind of discovery that can makes one’s day.

Footnote for ageing hippies She is the daughter of Sue Jones and Ravi Shankar, who had a big influence on George Harrison and, through him, the other members of the Beatles.

The worst worst case

As some countries are beginning to ‘re-open’ their economies because they seem to have the pandemic under some kind of control, I can understand the ubiquitous longing to get back to normal. Sadly, I don’t think that’s realistic for the time being. In fact it may be that we are only the beginning of the crisis. That’s because we’re in a cascade of inter-related crises: one is a health crisis, which is what has been grabbing most of the attention up to now; then there’s a looming economic crisis; and thirdly there’s political upheaval and culture warfare sparked by the murder of George Floyd. And, of course, for the UK there’s the added crisis attendant upon crashing out of the EU without a deal.

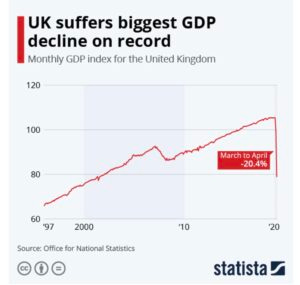

Now the economic impact of the pandemic is beginning to surface.

This is a picture of a particular economy falling off a cliff.

But actually, there’s a worse global scenario — that the banking system implodes again. This is the scenario outlined by Frank Portnoy from UC Berkeley in a long essay in The Atlantic. At the root of it is the addiction of the banks to a new kind of pernicious derivative product — collateralised loan obligations (CLOs).

“The financial crisis of 2008 was about home mortgages”, he writes.

Hundreds of billions of dollars in loans to home buyers were repackaged into securities called collateralized debt obligations, known as CDOs. In theory, CDOs were intended to shift risk away from banks, which lend money to home buyers. In practice, the same banks that issued home loans also bet heavily on CDOs, often using complex techniques hidden from investors and regulators. When the housing market took a hit, these banks were doubly affected. In late 2007, banks began disclosing tens of billions of dollars of subprime-CDO losses. The next year, Lehman Brothers went under, taking the economy with it.

The post-2008 reforms were well intentioned, says Portnoy, but…

They haven’t kept the banks from falling back into old, bad habits. After the housing crisis, subprime CDOs naturally fell out of favor. Demand shifted to a similar—and similarly risky—instrument, one that even has a similar name: the CLO, or collateralized loan obligation. A CLO walks and talks like a CDO, but in place of loans made to home buyers are loans made to businesses—specifically, troubled businesses. CLOs bundle together so-called leveraged loans, the subprime mortgages of the corporate world. These are loans made to companies that have maxed out their borrowing and can no longer sell bonds directly to investors or qualify for a traditional bank loan. There are more than $1 trillion worth of leveraged loans currently outstanding. The majority are held in CLOs.

It’s a long story, but the analogy with CDOs ie helpful. At the bottom of every CDO were sub-prime mortgages which had a high probability of default. At the bottom of every CLO are loans to companies which are in dire straits — and which were always in danger of failing even before Covid struck. But now many of them are terminally affected by the lockdown and are unlikely to return. So the CLOs for which they represented a manageable risk might suddenly start to look dodgy. And you can guess what would happen then.

The difference from 2008 is that national economies and central banks will not have the financial muscle to do another bailout.

Not a cheery read, but I think it’s important to get a perspective on the crisis we’re in.

US ‘policing’ is indeed disgraceful, but the UK has its problems too

Remember the Stephen Lawrence case — the inquiry into which confirmed that there was systemic institutional racism in the Metropolitan police.

People in glasshouses…

Europe resurfaces to find an odd mix of the familiar and the alien

This is wonderful. The New York Times sent a writer (Patrick Kingsley) and a photographer (Laetitia Vancon) to drive through Europe recording what they found. The result is an unmissable photo-essay, a reminder of the heyday of Life and the other mid-century news-magazines.

It also reminds me of the trip that Walker Evans and James Agee made in 1936 to report on the lives of poor sharecroppers in the Deep South which resulted in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

__________________________________________________________________________

The peer-reviewing crisis widens and deepens

Long and thoughtful essay by Milton Packer on the looming crisis in scientific publication processes.

Packer has been vocal for a long time on the deficiencies of peer-review. Long before the pandemic he has been criticising its capriciousness (as Rodney Brooks did in his essay that I blogged about yesterday), its biases towards supporting accepted dogma, the lack of consistent quality in the review process, and perverse incentives in editorial decision making.

He thinks — rightly IMHO — that these weaknesses of the peer-review process have been amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. To put it crudely, here’s been a kind of academic feeding frenzy. But Packer sees the recent scandal of the retraction of two papers published in leading journals as

a real opportunity for us to reinvent peer review. We needed to do so before the pandemic; we desperately need to do so now. We must implement changes that will provide confidence in the validity of published work, and we need to revamp and strengthen the peer-review and editorial decision-making processes. The FDA imposes severe penalties on site investigators who submit fabricated data; many journal editors follow a similar policy. Fear of a potentially career-ending ban on publications in leading journals will certainly motivate most corresponding authors to perform the exceptionally high level of due diligence that is needed to restore the trust that the review process desperately depends on.

If academic medicine does not make these changes, then we only have ourselves to blame when the credibility of medical research in the public’s view crumbles.

Yep.