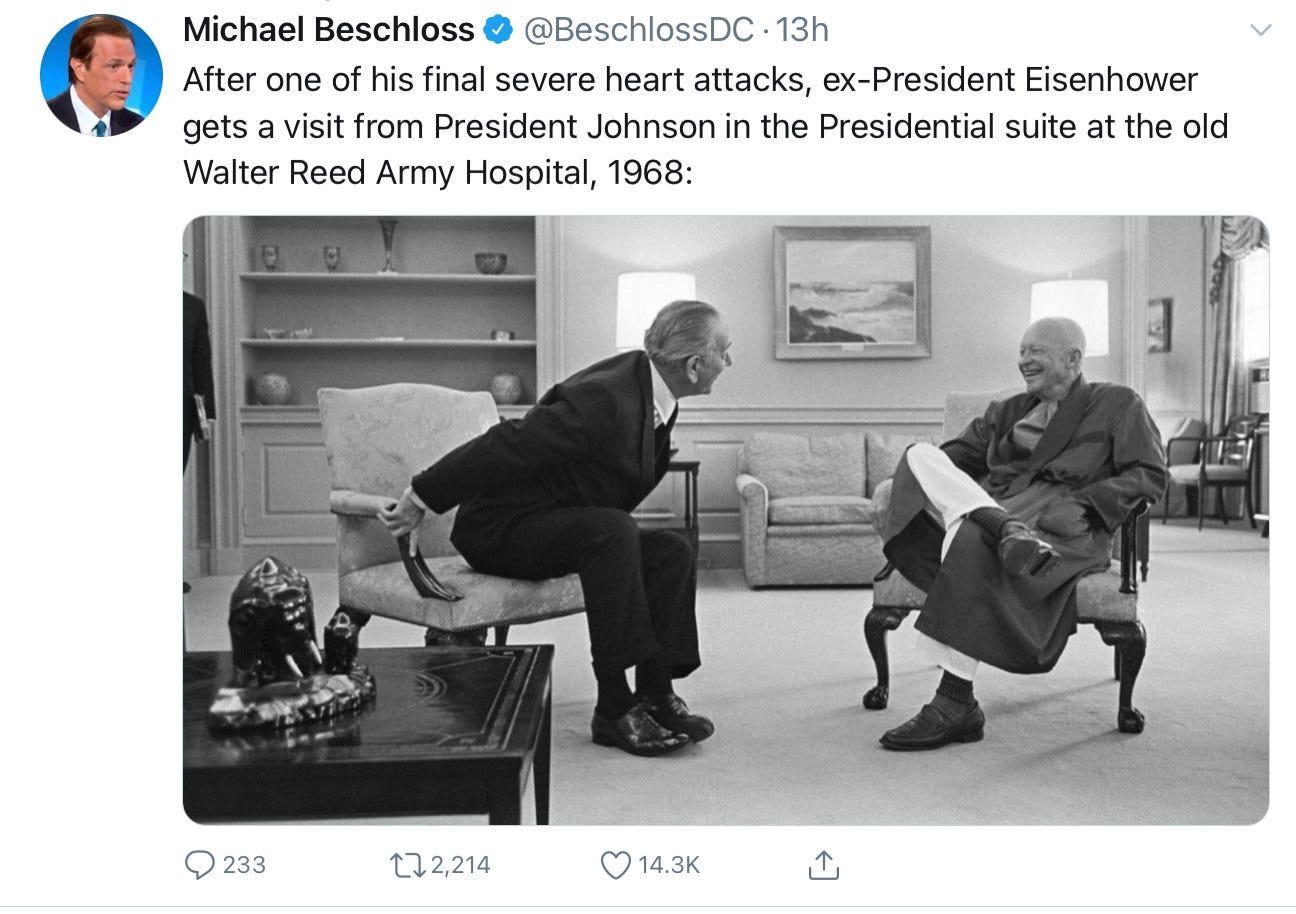

Ike and LBJ

I love this picture.

Quote of the Day

”More knowledge of a man’s real character can be gained by a short conversation with one of his servants than from a formal and studied narrative, begun with his pedigree and ended with his funeral.”

Samuel Johnson

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Diana Krall | Christmas Time Is Here

On balance, I thought it might be a good idea to play this before Christmas is cancelled again!

Long Read of the Day

What Google’s trending searches say about America in 2021

One of the most sobering books I’ve read is Seth Stephens-Davidowitz’s Everybody Lies: What the Internet can tell us about who we really are. He’s a data scientist who worked for a time at Google, where he learned that people’s Internet searches reveal things about them that they would never, ever entrust to another human being.

Which explains why at this time of the year there’s a good deal of interest in trying to extract meaning from records of what people have searched for most in the preceding twelve months. This piece on Vox by Rani Molla is the first compendium I’ve seen so far.

Each year, Google puts out lists of top trending searches in the United States, giving readers a tantalizing view into America’s collective id.

Rather than simply show what people searched for the most, these lists highlight the words and phrases people are searching for this year that they weren’t the year before. In effect, these searches speak to our latest fears, desires, and questions — the things we were too embarrassed to ask anyone but Google.

As Google data editor Simon Rogers put it to me last year, “You’re never as honest as you are with your search engine. You get a sense of what people genuinely care about and genuinely want to know — and not just how they’re presenting themselves to the rest of the world.”

The lists are, as you’d expect, all over the place, but Molla notes a few common themes that rose to the top, “offering a glimpse of what it was really like to be an American in 2021”.

Do read the whole thing.

Wikipedia (contd.)

My mini-rant about Wikipedia yesterday has sparked several interesting emails, for which many thanks. They prompted me to reflect on why I value it so much, and why I think it’s such an amazing phenomenon.

Two thinkers set me off on this track, many years ago. One was James Boyle, a great legal scholar who gave a lecture at my invitation in Cambridge on the significance of the public domain in a networked world. (James was one of the founders of Creative Commons, and his 2009 book — The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind — is a masterful survey of the enclosure of the digital commons.) In his Cambridge lecture, he highlighted the improbability of a project like Wikipedia getting off the ground and prospering. Crudely paraphrased, his thought-experiment went roughly like this: “What, you mean anyone can write and edit entries? Anyone????? C’mon, give me a break”. This was the origin of the old joke about the project: that Wikipedia works really well in practice, just not in theory.

The second wake-up call (for me) came from Jonathan Zittrain’s book (also published in 2009), The Future of the Internet, and How to Stop It. One of the most striking things about the book was the amount of attention he paid to the governance structures of Wikipedia — in particular the elaborate process of discussion that goes into editing entries, resolving arguments, the fact that the revision history of every entry is publicly available etc. Why did these people — all unpaid volunteers — create such an elaborate structure?

The answer of course is that they somehow intuited that we would be moving into the polarised world we now inhabit — where lies, propaganda, misinformation, etc. would become rife, and where people felt entitled not only to their own opinions but also their own facts. And in fact, if anyone’s interested in knowing how best to work within this social-media-fuelled maelstrom, then the Wikipedia methodology provides a useful way through it.

The big thing about Wikipedia, though, is that it’s the only surviving illustration of how the early promise of the Internet — that it could harness the collective IQ of humankind — might be realised. As I write, it’s the seventh most-visited site on the Web and the only non-commercial site in the top 100. In other words, it’s one of the wonders of our networked world.

Apple’s sweetheart deal with the Chinese state

An interesting story that broke in The Information this week says that Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, signed a secret $275 billion deal with China in 2016 to neutralise threats that would have hobbled its devices and services in the country.

According to the Guardian’s report,

The five-year agreement was made when Cook paid visits to China in 2016 to quash a host of regulatory action against the company, the report said, citing interviews and internal Apple documents.

Cook lobbied Chinese officials, who believed the company was not contributing enough to the local economy, and signed the agreement with a Chinese government agency, making concessions to Beijing and winning important legal exemptions, the report added.

Some of Apple’s investment in China would go toward building new retail stores, research and development centers and renewable energy projects, the report said, citing the agreement.

The most interesting revelation, though, was this:

“Outside of the deal, Apple made other concessions with the Chinese government to keep business running. By early 2015, China’s State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping had directed Apple Maps to make the Diaoyu Islands, or Senkaku Islands, which China and Japan both claim to own, look big even when zoomed out; regulators said they’d refuse to approve the Apple Watch if Apple didn’t comply, according to internal documents viewed by The Information.”

When you sup with the Devil, best to use a long spoon. And don’t navigate using Apple Maps when travelling in that part of the globe?

I wonder what effect, if any, these revelations will have on the sainted Cook’s reputation.

My commonplace booklet

How to read canonical literature

Tyler Cowen is one of the most omnivorous readers I’ve come across. Someone asked him how he does it. Here’s the gist of his answer:

Assume from the beginning that you will need to read the work more than once, or at least read significant portions of the work more than once. Furthermore, these multiple readings should be done back-to-back (and also over many years, btw, after all this is the canonical). So your first reading should not in every way be super-careful, as you don’t yet know what to look for. Treat the first reading as a warm-up for the second reading to follow.

The first fifty pages very often should be read twice, in a single sitting if possible, even on your “first reading.”

Assemble three to five guides to the main book you are reading, or significant fairly general contributions to the secondary literature. Consult those works throughout, and imbibe an especially large dose of them between your first and second readings of the classic itself. But you shouldn’t necessarily read those books straight through, or finish them. They are to be pillaged for both conceptual structure and particular insights, not to be reified as books in their own right.

Always be asking yourself how the classic work you are reading is engaging with other classic works you might know or know of. Starting with the Bible, but not ending there.

Find people to talk to about the book.

He missed out the sixth and most important rule: arrange for the day to be redefined as 36 hours. Oh – and give up on sleep: it’s a waste of valuable reading time.